20 Jun Timely, transparent, targeted? Government communications during the pandemic

Pandemics are nothing new, as Viktoria Adler and Diotima Bertel reminded us in this article. False and misleading information didn’t wait for the 21st century either. Long before we started talking about “fake news”, Daniel Defoe noted in his 1722 Journal of the Plague Year, “The plague was itself very terrible, and the distress of the people very great… But the rumour was infinitely greater”.

The subjects of the rumours over the centuries are familiar too. Nothing as sophisticated as “it’s all a plot to inject us with microchips”, but blaming minorities figured prominently, and thousands of Jewish men, women and children were massacred in Europe during the Black Death. As you’d expect, fake cures soon appeared too. Nobody thought of drinking bleach, but vinegar as well as “plague waters” and powders were popular, like the one in this advert from the British Library’s collections (which helpfully advises “sweating carefully”).

Image source

An epidemic then is not simply a medical phenomenon, and to deal with it, you have to understand how human behaviour is affected by multiple subjective influences. It should come as no surprise that as their situation becomes more desperate, people panic, and their hopes start to move from science to superstition.

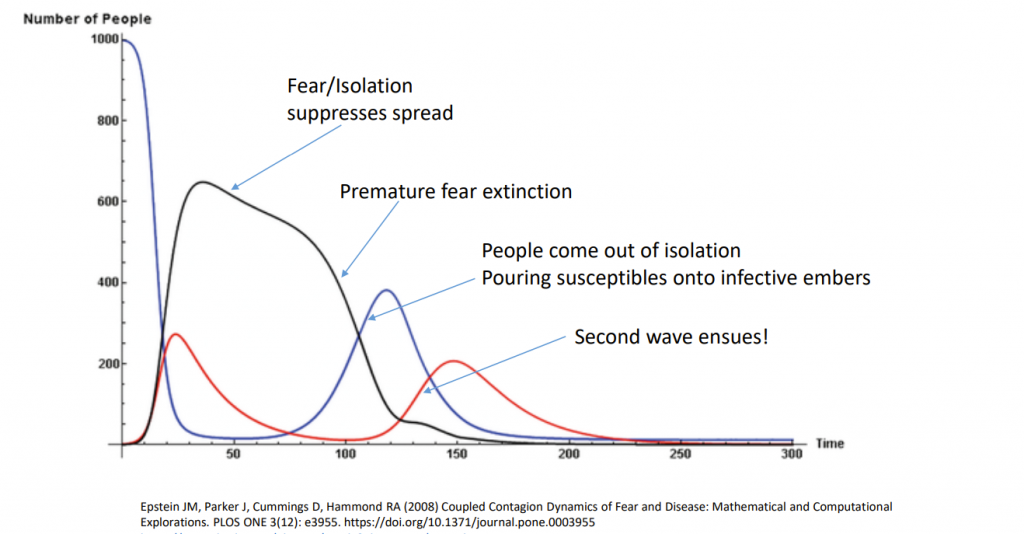

Already in 2008, epidemiologist Joshua Epstein modelled the way in which biology and psychology interact during disease outbreaks. At a conference organised by the OECD New Approaches to Economic Challenges unit in March 2020, he showed how epidemic “waves” can form simply through the interplay of contagion as such, and fear of contagion. Initially, fear and isolation slow the spread, but when fear drops to a certain level, complacency leads to a resurgence of the disease as people abandon precautionary measures.

Image source

Who and what people believe determines whose and what advice they will follow. Faced with a national emergency, governments took the lead in responding to Covid-19, but they were competing in a crowded information marketplace. COVINFORM compared the communication strategies of 15 European countries plus the UK, Israel and the United States to see what lessons can be learned. The results of the research are still being analysed, but some conclusions can be drawn. A good communication strategy needs to be timely, transparent and targeted. The governments examined certainly aimed for this, but how well they succeeded varies considerably.

In part, this is because the context was so difficult. Communication depends on trust, and trust in government, indeed in institutions generally, had been declining for a number of years before the Covid outbreak. The pandemic amplified this. The 2021 Edelman Trust Barometer goes so far as to talk of “a failing trust ecosystem unable to confront the rampant infodemic, leaving the four institutions – business, government, NGOs and media – in an environment of information bankruptcy…”.

Many governments tackled the trust deficit by using experts rather than politicians to present information. One surprise is that in the age of social media, the old-fashioned press conference remained a powerful tool, and in many cases the experts appearing at them became nationally-respected figures. Even so, there was still the fact that while people want “scientific” advice, they do not necessarily understand how that advice is generated and why it changes, often radically and rapidly, as new data become available. One lesson, therefore, is the need for a strategy to deal with uncertainty. There needs to be more clarity too about the responsibilities of government, health authorities, and experts, who may disagree with each other.

Scientific advice on how to get the messages across should have been mobilised far more. The lack of engagement of behavioural and communication scientists in crafting communication strategies meant that often the campaigns did not have the impact hoped for. The lack of a strategy against misinformation was also a handicap. Data from Spain for instance show a correlation between interest in fake news and the increase in deaths from Covid-19. (Have a look at our knowledge repository[1] for resources on misinformation).

We’ll get back to you soon with the full results of the study, and a set of recommendations on how to make reliable information greater than the rumour. To stay updated follow us on Twitter, LinkedIn and Facebook.

Author: Patrick Love